| 中文|ENGLISH |

|

| British screenwriters adapting China- based Judge Dee novels for mainland TV |

|

In 2013, following a full year of negotiations with the author’s son, Beijing-based producer Wang Donghui secured the rights to make a Chinese television series based on Dutch diplomat Robert van Gulik’s series of Judge Dee historical mystery novels. He also had one of China’s biggest TV stars, Zhang Jiayi, on board as his producing partner and to play Judge Dee. With the huge popularity of crime shows such as Sherlock and CSI on Chinese streaming sites, Wang believed he had the beginnings of a popular historical detective series that could raise Chinese-language television to the level of premium cable drama in the West. But who could write it? Nobody in China had that kind of experience. “I looked at writers in both America and Britain – but while American writers are good at scale and structure, British writers excel in character development and that’s what I needed for this project,” explains Wang, who worked at Creative Artist Agency (CAA)’s Beijing office before launching production outfit Combo Drive Pictures. He started firing off emails to writers he admired, including Jim Keeble and Dudi Appleton, whose credits include writing Thorne, for Sky1, and Silent Witness, for the BBC. But it took a long time before anybody took him seriously. It wasn’t until British talent agent Tor Belfrage visited Beijing and met Wang in 2014 that the ball started rolling. She immediately contacted Keeble and Appleton’s agents, saying: “Will you answer this guy’s emails? He’s for real!” Wang then sat down with the two writers and their partner in 87 Films, producer Patrick Irwin, in London, bringing along John Woo Yu-sen’s long-time producing partner Terence Chang Chia-chen for additional credibility and moral support. Wang had just come off producing critically acclaimed martial arts drama Brotherhood Of Blades with China Film Group, which was executive produced by Chang.

Actor Zhang Jiayi is flanked by actresses Yan Ni (left) and Jiang Shuying at a Beijing press conference for Servant of Two Masters in August, 2013. Picture: Alamy

“At first we were thinking, ‘Why would we do this?’ But we were impressed by the ambition of it,” recalls Appleton, of their initial meeting. “He was saying he had the money to get this made, then sell to Chinese broadcasters later. That made no sense to us – there would have to be some ridiculous upside to do it that way. But then he told us that Zhang Jiayi’s last show had 120 million viewers and we were, like, OK we see the upside!” Filming first and selling to broadcasters and online video platforms later is a fairly standard way of producing TV shows in the mainland, especially now that intense competition between streaming sites is driving up prices. “Dee’s stories have always been popular in China and have already been featured in TV series, although none has been based on van Gulik’s books,” says Wang, explaining what gave him the confidence to finance the series. “And having Zhang Jiayi on board producing the show with me makes it an even easier sell.” Written in English in the 1950s and 60s, the Judge Dee mysteries follow the exploits of a semi-fictional Tang dynasty (AD600-900) magistrate, who van Gulik first stumbled across in an 18th-century Chinese novel. “They have a slight Raymond Chandler feel to them that gave them enough edge that we could see what we could bring to it,” says Appleton. The challenge then was how to transform 36 books – often with three interweaving crime cases in each – into 40 episodes of television. The team decided to focus on just one story in each hour of television – often prising apart the interweaving stories from the books – but with a serial element running throughout.

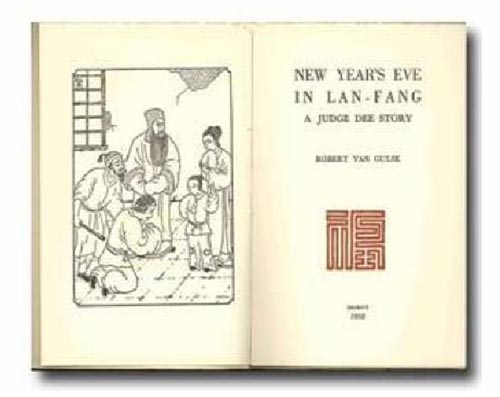

A 1958 edition of Robert van Gulik's Judge Dee novel New Year's Eve in Lan-Fang.

“Donghui really wanted this to feel like a serial, so the audience could build their knowledge of the main character and his team,” explains Keeble. “We talked about what we could introduce and came up with the notion of a father who disappeared when Dee was 10. So there’s an overarching mystery in the sense of loss and abandonment that drives Dee.” A team of about 14 writers are working on the show, with Keeble, Appleton and script editor Andrew Clifford also writing their own episodes. Early drafts are sent to Wang for his notes on cultural differences, standard queries on the characters’ motivations and potential censorship issues. “What he doesn’t try to do is second guess you – he does his job as a producer,” says Appleton. “Often producers think their job is to be the stupidest member of the audience, whereas he gets that he’s trusting us to write this. If there’s something he thinks doesn’t work, he’ll just tell you it doesn’t work.” When the English scripts are completed, Wang has them translated and brings in a Chinese scriptwriter to “polish them in terms of dialogue and cultural issues”. As the series is historical, and set during the Tang dynasty, which is especially revered in Chinese history, there are fewer potential censorship issues than with a contemporary drama. “There are limits on nudity and sex scenes in Chinese television, but I’ve been encouraging Jim and Dudi to explore issues such as homosexuality and drug use,” says Wang. Another issue for both the London and Beijing teams was how to set up a payment structure that everybody was happy with. Irwin suggested setting up a British company, which Wang could then transfer money into to pay the writers. “It means that we’re all above board as far as UK tax goes,” explains Irwin. “It’s a fairly front-loaded structure as it would be difficult to see any further money as far as [Chinese] exploitation goes. But if there’s any life for the series outside of China, Donghui is open to talking to us about that.” With such a large potential audience in China, international exploitation has not been a key consideration for the series. The character of Judge Dee is not well known outside China, although Granada TV featured him in a 1969 TV series, with a heavily made-up British actor, Michael Goodliffe, playing Dee. But the team is also aware that a growing number of high- quality foreign-language TV shows are starting to cross borders and, as Keeble observes, “The audience is hungry for content and worlds they don’t know very well.” Wang is aiming to start pre-production on the show before the end of the year and is eyeing Luoyang, in Henan province, the former capital of the Tang dynasty, as one of the main locations. Although he’s enjoyed the experience, he explains that Chinese broadcasters usually demand very long-running series – 60 to 80 episodes – so it’s extremely time- consuming to produce anything of superior quality at that length. “I don’t think I’ll have time to do another TV series as it’s taken me four years up until now and will take another two years to finish production,” says Wang. “But I have several film projects in development and I think there’s huge potential for UK writers working on Chinese movies. I’m already talking with several UK writers to develop one of my film projects.”

|

Copyright © 2009 - 2017 CDP All Rights Reserved

网站制作:沈阳全景网络科技www.024360.com